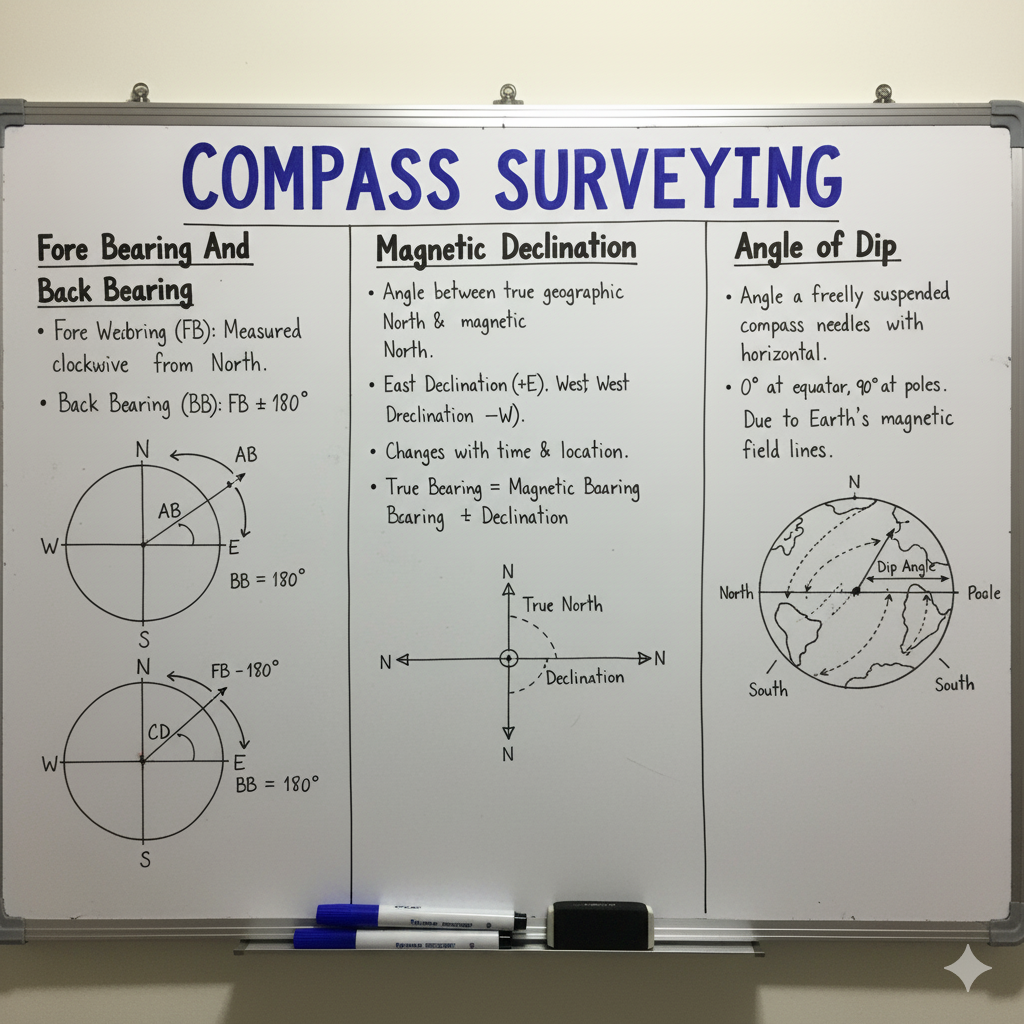

In compass surveying, accurately determining the direction of survey lines is as critical as measuring their lengths. This infographic explores key directional concepts: Fore Bearing and Back Bearing, how they relate to calculating included angles, the phenomenon of Magnetic Declination, and the Angle of Dip. Understanding these principles is essential for precise land measurements, map creation, and ensuring the reliability of survey data in civil engineering projects.

Fore Bearing (FB) & Back Bearing (BB)

Bearings define the direction of a line relative to a meridian. Fore Bearing and Back Bearing describe the direction of a single line viewed from its two ends.

| Concept | Definition | Relationship | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fore Bearing (FB) | The bearing of a survey line measured in the direction of the progress of the survey (e.g., from station A to station B). | FBAB | A → B |

| Back Bearing (BB) | The bearing of the same survey line measured in the opposite direction (e.g., from station B to station A). | BBAB = FBAB ± 180° (+ if FB < 180°, – if FB > 180°) |

B → A |

| Check for Local Attraction | In the absence of local magnetic disturbances, the difference between FB and BB of a line should be exactly 180°. | If FB – BB ≠ 180°, local attraction is present at one or both stations. | FB – BB = 180° (No LA) |

Calculating Included Angles in Traverse

Included angles are the interior or exterior angles formed by adjacent lines in a traverse. They are crucial for checking the angular accuracy of a closed traverse.

| Angle Type | Calculation Method | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Interior Angle |

|

Sum of interior angles of an n-sided polygon = (2n – 4) × 90° |

| Exterior Angle | Exterior Angle = 360° – Interior Angle. | Sum of exterior angles of an n-sided polygon = (2n + 4) × 90° |

Magnetic Declination: True vs. Magnetic North

Magnetic declination is the horizontal angle between the True Meridian (geographical North-South) and the Magnetic Meridian (direction shown by a compass needle). It is a critical parameter as it directly impacts the conversion between magnetic and true bearings.

| Concept | Description | Formula for True Bearing |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The angular difference between the true north (geographic) and magnetic north. | True Bearing = Magnetic Bearing ± Declination |

| Eastern Declination | When the Magnetic North is to the East of the True North. | True Bearing = Magnetic Bearing + Eastern Declination N ↑ T.N. / M.N. |

| Western Declination | When the Magnetic North is to the West of the True North. | True Bearing = Magnetic Bearing – Western Declination T.N. ↑ N / M.N. |

| Secular Variation | Slow, long-term changes in declination over centuries, often completing a cycle in several hundred years. | Requires historical data for correction. |

| Diurnal Variation | Regular daily fluctuations in declination, typically small (5-15 minutes of arc), influenced by solar radiation. | Varies throughout the day. |

| Annual Variation | Small, cyclical changes over a year, superposed on secular variation. | Minor, generally ignored for most practical surveys. |

| Irregular Variation | Sudden, unpredictable changes due to magnetic storms or solar flares. | Can significantly affect readings; surveying should be avoided during such events. |

Angle of Dip: Vertical Component of Earth’s Magnetism

The angle of dip (or magnetic dip) is the vertical angle that the Earth’s magnetic field lines make with the horizontal plane at any given location. It is a fundamental characteristic of the Earth’s magnetic field.

| Concept | Description | Variation & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The angle between the direction of the Earth’s magnetic field lines and the horizontal plane. A freely suspended magnetic needle will dip towards the Earth. | ↓ (N. Pole) ― (Equator) ↑ (S. Pole) |

| Causes | Caused by the non-uniform nature of the Earth’s magnetic field, which is not parallel to the Earth’s surface except at the magnetic equator. | Varies from 0° at the magnetic equator to 90° at the magnetic poles. |

| Impact on Compass | A well-balanced compass needle is designed to remain horizontal. However, due to dip, one end of the needle may be heavier, causing it to tilt. | Compasses used in different latitudes require balancing weights (riders) to counteract the dip and keep the needle horizontal for accurate readings. |

GATE Exam Practice Questions & Explanations

Test your understanding of Bearings, Declination, and Angle of Dip with these practice questions, commonly encountered in civil engineering competitive exams like GATE.

1. If the Fore Bearing of a line AB is 150°, what is its Back Bearing?

Answer: 330°

Since FB < 180°, BB = FB + 180° = 150° + 180° = 330°.

2. The True Bearing of a line is N30°E. If the magnetic declination is 5° West, what is the Magnetic Bearing?

Answer: N35°E

If declination is West, True Bearing = Magnetic Bearing – Western Declination. So, Magnetic Bearing = True Bearing + Western Declination = 30° + 5° = 35°E (in NE quadrant).

3. Which of the following variations in magnetic declination is a long-term change spanning centuries?

Answer: Secular Variation

Secular variation describes the slow, continuous, and non-periodic change in magnetic declination over long periods, often completing a cycle over hundreds of years.

4. At the magnetic equator, what is the angle of dip?

Answer: 0°

At the magnetic equator, the Earth’s magnetic field lines are parallel to the horizontal surface, resulting in zero angle of dip.

5. If the FB of line PQ is 45° and its BB is 224°, what does this indicate?

Answer: Presence of local attraction at one or both stations.

The difference between FB and BB should be exactly 180° (45° + 180° = 225°). Since 224° is not 225°, local attraction is present.

6. The sum of interior angles of a closed traverse with ‘n’ sides should ideally be:

Answer: (2n – 4) x 90°

This is the fundamental geometric condition for the angular closure of any closed polygon traverse.

7. When the magnetic north is to the East of the true north, the declination is termed as:

Answer: Eastern Declination

This is the definition of Eastern Declination, where true bearing is obtained by adding the declination to the magnetic bearing.

8. What is the approximate range of diurnal variation in magnetic declination?

Answer: 5-15 minutes of arc

Diurnal variation refers to the small, regular daily fluctuations influenced by the sun, typically within this range.

9. If a magnetic compass needle, perfectly balanced, is brought to a magnetic pole, it would:

Answer: Stand vertical (dip 90°)

At the magnetic poles, the Earth’s magnetic field lines are perpendicular to the horizontal surface, causing a 90° angle of dip.

10. The Bearing of a line AB is N60°W. Its Whole Circle Bearing (WCB) is:

Answer: 300°

In the NW quadrant, WCB = 360° – Reduced Bearing = 360° – 60° = 300°.

11. If the True Bearing of a line is 210° and the Magnetic Bearing is 200°, the magnetic declination is:

Answer: 10° East

True Bearing = Magnetic Bearing + Eastern Declination. So, Declination = True Bearing – Magnetic Bearing = 210° – 200° = 10° East.

12. The included angle at a station in a traverse is measured as the angle between:

Answer: The preceding line and the succeeding line.

Included angles are formed by two adjacent lines of a traverse, always measured from the previous line to the next line in the direction of traverse.

13. Which of the following affects magnetic declination but is generally ignored in ordinary surveys due to its minor effect?

Answer: Annual Variation

Annual variation is a small, yearly oscillation of declination, usually insignificant for routine survey work compared to secular and diurnal variations.

14. What is the purpose of adding balancing weights (riders) to a compass needle?

Answer: To counteract the angle of dip and keep the needle horizontal.

Riders are used to balance the needle against the Earth’s magnetic dip, which can cause one end of the needle to tilt downwards in different latitudes.

15. If the FB of a line is 300°, its RB (Reduced Bearing) is:

Answer: N60°W

300° is in the NW quadrant. RB = 360° – 300° = 60°. So, N60°W.

16. The phenomenon causing a magnetic needle to deviate from the true magnetic meridian due to local influences is called:

Answer: Local Attraction

Local attraction is caused by magnetic substances like iron or steel objects, affecting the accuracy of compass readings at a specific station.

17. If a traverse runs anti-clockwise, the interior angle at a station is calculated as:

Answer: FB of next line – BB of previous line

This formula ensures the correct calculation of interior angles for anti-clockwise traverses, maintaining consistency in angular closure checks.

18. True Meridian is determined by:

Answer: Astronomical observations

True meridian is a fixed geographical line derived from astronomical observations of celestial bodies, unlike magnetic meridian which varies.

19. At the magnetic poles, the angle of dip is:

Answer: 90°

At the magnetic poles, the Earth’s magnetic field lines are perpendicular to the horizontal, causing the needle to dip completely vertically.

20. What type of variation in magnetic declination is sudden and unpredictable?

Answer: Irregular Variation

Irregular variations are caused by magnetic storms or solar flares and cannot be predicted or easily corrected, making surveying unreliable during such events.