In surveying, no measurement is perfectly exact; every observation is subject to a degree of uncertainty. The Theory of Errors provides a systematic framework for understanding, analyzing, and quantifying these inevitable discrepancies. For civil engineers, mastering error theory is crucial for ensuring the precision and reliability of spatial data, which forms the bedrock of design, construction, and infrastructure management. This infographic explores error types, their sources, methods for weighting observations, and techniques for estimating probable errors in computed results.

Introduction to the Theory of Errors

The Theory of Errors is a statistical discipline concerned with the mathematical analysis of errors in observations. Its necessity arises from the fact that all measurements, regardless of the instrument or care taken, contain errors.

The primary objective is not to eliminate all errors (which is impossible), but to **detect, minimize, and quantify their impact** on survey results. This allows engineers to determine the most probable values of measured quantities and assess the confidence in their final outcomes.

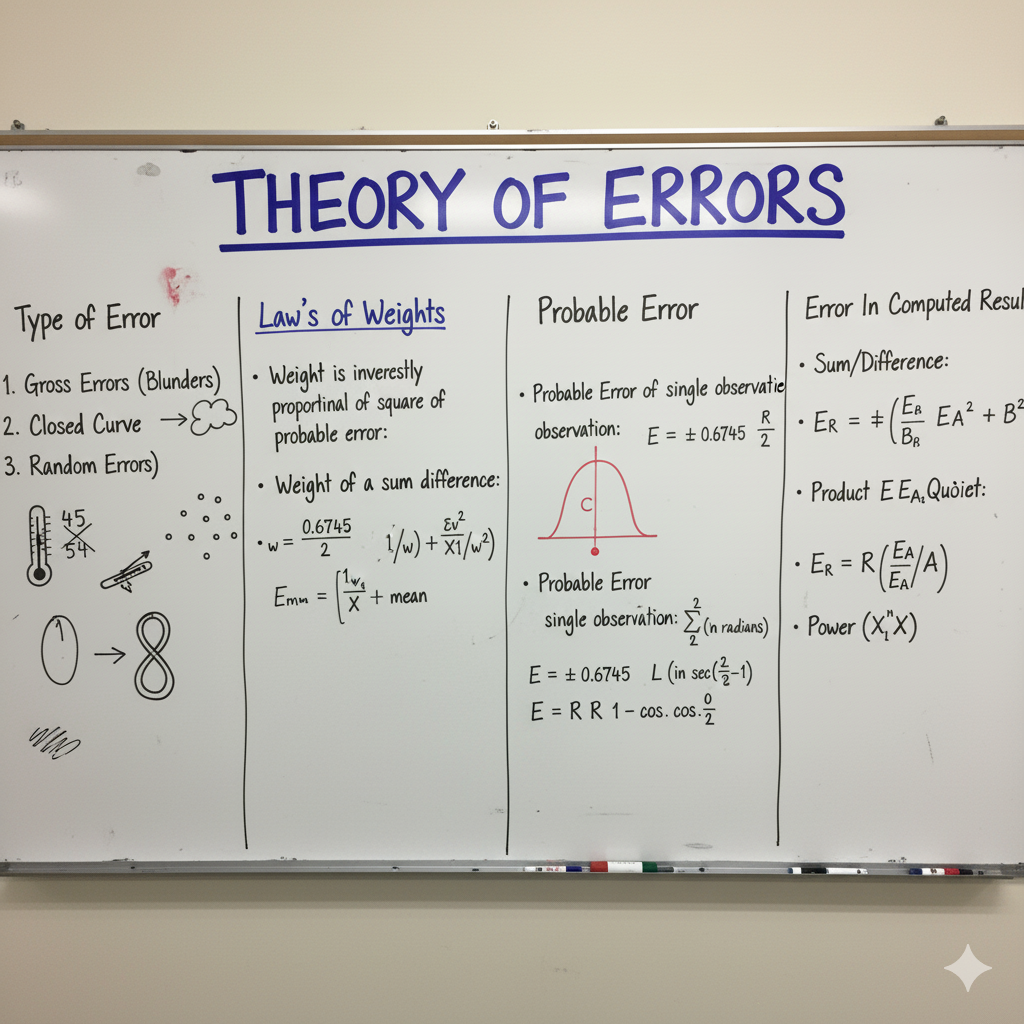

Classification of Errors in Surveying

Errors in surveying measurements are typically classified into three main categories based on their characteristics and behavior.

| Error Type | Description & Characteristics | Nature & Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Gross Errors / Mistakes | Large errors resulting from carelessness, misunderstanding, fatigue, or poor judgment by the observer. They are often detected through checks and discrepancies. | Unpredictable, large in magnitude. Must be detected and eliminated by re-observing or re-calculating. |

| Systematic Errors / Cumulative Errors | Errors that follow a consistent pattern and magnitude, always having the same sign (+ or -) under similar conditions. They accumulate over a series of measurements. | Predictable, cumulative. Can be corrected by applying formulas, calibration, or adopting specific field procedures. |

| Accidental Errors / Random Errors | Errors that remain after gross and systematic errors have been eliminated. They are unpredictable, vary in sign and magnitude, and obey the laws of probability. | Unpredictable, compensating (tend to cancel out over many observations). Cannot be eliminated but can be minimized by precise methods and multiple observations. |

Primary Sources of Errors

Errors can originate from the instruments used, the surrounding environment, or the human factor involved in the measurement process.

| Source | Examples | Corresponding Error Type (primarily) |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumental Errors | Imperfect instrument calibration, faulty construction, wear and tear (e.g., tape too long/short, collimation error in level). | Systematic Errors |

| Natural Errors | Variations in natural phenomena (e.g., temperature, humidity, atmospheric refraction, wind, gravity, sun’s glare). | Systematic and/or Accidental Errors |

| Personal Errors | Limitations of human senses, carelessness, fatigue, improper handling of instruments (e.g., misreading a scale, inaccurate centering, not holding staff vertical). | Gross Errors / Mistakes and Accidental Errors |

Laws of Weights: Quantifying Observation Reliability

In precise surveying, not all observations are considered equally reliable. The ‘weight’ assigned to an observation indicates its relative precision or trustworthiness.

Concept of Weight (w)

The weight of an observation is inversely proportional to its variance (or square of its probable error). A higher weight implies a more precise or reliable observation.

w ∝ 1 / σ2 ∝ 1 / (Probable Error)2

Weighted Arithmetic Mean:

When observations have different weights, the most probable value is their weighted arithmetic mean.

Weighted Mean (Xw) = Σ(wiXi) / Σwi

Laws of Weights:

- The weight of an arithmetic mean of several observations is equal to the sum of the weights of the individual observations.

- The weight of a quantity multiplied by a constant is inversely proportional to the square of that constant.

- The weight of a sum or difference of independent quantities is found by various combinations based on their individual weights (e.g., 1/W = 1/w1 + 1/w2).

Probable Error (P.E.): Quantifying Uncertainty

Probable error is a statistical measure of precision, defining a range within which there is a 50% probability that the true value lies. It’s particularly useful for accidental errors.

| Concept | Description | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Probable Error of a Single Observation (Ps) | The value such that there is an equal chance (50%) that the true error of a single observation will be greater or less than Ps. | Ps = ± 0.6745 × σ (where σ is standard deviation) |

| Probable Error of the Arithmetic Mean (Pm) | The value such that there is an equal chance (50%) that the true error of the arithmetic mean of a series of observations will be greater or less than Pm. | Pm = ± 0.6745 × σ / sqrt(n) (where n is number of observations) |

| Relationship to Standard Deviation | Probable error is directly proportional to standard deviation, a more common measure of spread. | P.E. ≈ 2/3 σ |

Error in Computed Results

When a final result is derived from multiple measurements, the error in the result depends on the errors in the individual measurements.

| Computed Result Type | Error in Result (Probable Error) | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Sum or Difference (Z = A ± B) | PZ = ± sqrt(PA2 + PB2) | A and B are independent measurements with probable errors PA and PB. |

| Product (Z = A × B) | PZ / Z = ± sqrt[ (PA/A)2 + (PB/B)2 ] | A and B are independent measurements with probable errors PA and PB. |

| Series of Measurements | If an operation is repeated ‘n’ times (e.g., chaining a long line in ‘n’ equal sections). | Error ∝ sqrt(n) for random errors. Error ∝ n for systematic errors. |

General Principles for Error Management in Surveying

Effective error management requires adherence to key principles during planning, fieldwork, and data processing.

- Work from Whole to Part: Establish primary control with high precision, then proceed to secondary and tertiary controls with lesser precision. This localizes errors.

- Independent Checks: Every measurement should be checked by an independent observation or calculation to detect mistakes and systematic errors.

- Balancing of Errors: For closed traverses, angular and linear errors must be adjusted to distribute discrepancies proportionally among measurements.

- Knowledge of Instrument: Understand the limitations, precision, and potential systematic errors of each instrument used.

- Proper Field Procedures: Adhere strictly to standardized field procedures to minimize personal and systematic errors.

- Multiple Observations: Taking multiple observations and averaging them helps in minimizing the effect of accidental errors.

GATE Exam Practice Questions & Explanations

Test your understanding of the Theory of Errors with these GATE-style questions, critical for evaluating survey precision and reliability.

1. Errors in surveying measurements that have a constant magnitude and always the same sign are known as:

Answer: Systematic Errors

Systematic errors are predictable, cumulative, and can often be corrected by formula or specific procedures.

2. Which type of error obeys the laws of probability and tends to cancel out over a series of observations?

Answer: Accidental Errors (Random Errors)

Accidental errors are unpredictable in sign and magnitude and compensate each other over multiple measurements.

3. Misreading a staff during levelling is an example of a:

Answer: Gross Error (Mistake)

Gross errors are large, avoidable errors due to carelessness or misunderstanding, typically detected by checks.

4. The weight assigned to an observation is inversely proportional to the:

Answer: Square of its probable error (or variance)

A higher weight indicates greater precision and trustworthiness of the observation.

5. If the probable error of a single observation is Ps, what is the probable error of the arithmetic mean of ‘n’ observations?

Answer: Ps / sqrt(n)

The precision of the mean increases with the square root of the number of observations, thus its probable error decreases by that factor.

6. The error due to a tape being too long is a:

Answer: Systematic Error

This error is consistent and predictable (always making measured distances appear shorter than true), hence systematic.

7. The formula for the probable error of the sum or difference of two independent quantities A and B with probable errors PA and PB is:

Answer: ± sqrt(PA2 + PB2)

This formula is used to propagate probable errors when quantities are added or subtracted.

8. Which source of error includes variations in temperature and atmospheric refraction?

Answer: Natural Errors

These are external environmental factors that influence measurements.

9. The principle of ‘Working from Whole to Part’ in surveying is primarily adopted to:

Answer: Localize and prevent the accumulation of errors.

By establishing high-precision control points first, errors in smaller, detailed surveys are contained within those sections.

10. If the standard deviation of a series of observations is ‘σ’, the probable error of a single observation is approximately:

Answer: 0.6745 × σ

This is the constant factor relating probable error to standard deviation for a normal distribution.

11. A fault in the calibration of a surveying instrument is a type of:

Answer: Instrumental Error

These errors arise from imperfections in the design, manufacture, or calibration of the measuring device.

12. The most probable value of a quantity when multiple observations with different weights are taken is its:

Answer: Weighted Arithmetic Mean

The weighted mean gives more significance to observations deemed more reliable (higher weight).

13. The standard deviation is a measure of:

Answer: The spread or dispersion of data points around the mean.

It quantifies how much individual data points deviate from the average value.

14. If a certain measurement is repeated ‘n’ times, the accidental error in the final result will be proportional to:

Answer: sqrt(n)

Accidental errors tend to compensate, so their effect grows with the square root of the number of repetitions, not linearly.

15. The primary goal of applying the Theory of Errors in surveying is to:

Answer: Quantify the reliability and precision of survey results.

While minimizing errors is important, the theory provides a statistical basis for assessing the confidence in the final measurements.

16. An error that is constant in magnitude and sign for a given set of conditions is:

Answer: Systematic error

This consistent behavior distinguishes systematic errors from random or gross errors.

17. Which principle states that every measurement should be verified by another independent observation?

Answer: Independent Checks

This principle is crucial for detecting mistakes and verifying the accuracy of the primary measurements.

18. The effect of parallax error in telescope sighting is classified under which source of error?

Answer: Personal Error

Parallax error arises from improper focusing by the observer, making it a human-induced error.

19. If a quantity Z is computed as Z = A / B, and PA and PB are probable errors of A and B, the relative probable error of Z is related by:

Answer: (PZ/Z) = ± sqrt[ (PA/A)2 + (PB/B)2 ]

For products and quotients, the squares of the relative probable errors are combined.

20. What is the fundamental difference between accidental errors and systematic errors?

Answer: Accidental errors are unpredictable and compensating, while systematic errors are predictable and cumulative.

This distinction dictates how each type of error is handled and corrected in surveying computations.