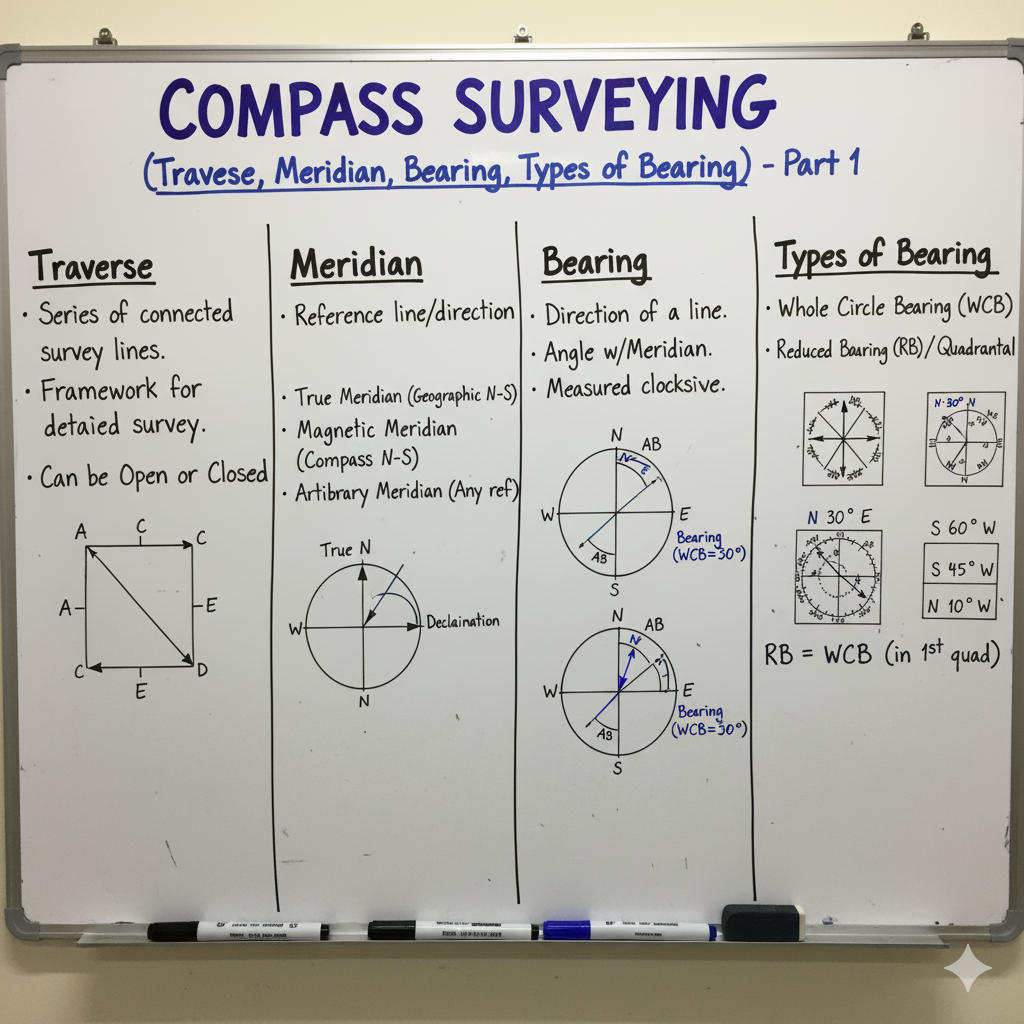

Compass surveying is a crucial method in civil engineering for determining the relative positions of points by measuring both linear distances and angular directions. It primarily relies on a magnetic compass to establish the direction of survey lines, forming a ‘traverse’. This infographic delves into the core concepts of compass surveying, including different types of meridians, bearing systems, traverse classifications, and methods to account for local magnetic disturbances.

Understanding Compass Surveying

Compass surveying is a type of surveying where the direction of a survey line is determined by magnetic compass, and the length of the line is measured with a chain or tape. It is particularly suitable for large areas where rapid data collection is prioritized over extreme precision, or where obstacles prevent the use of other methods like chain surveying alone. Its primary principle involves measuring angles with respect to a magnetic meridian.

Meridians: Reference Lines for Direction

A meridian is a fixed reference line used to define the direction or bearing of a survey line. Different types of meridians are used depending on the purpose and accuracy requirements of the survey.

| Meridian Type | Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| True Meridian | A line passing through the geographical North and South poles and any point on the Earth’s surface. It is a fixed and unchangeable line. | Fixed direction, used for astronomical observations, basis for maps. |

| Magnetic Meridian | The direction indicated by a freely suspended and balanced magnetic needle unaffected by local attractive forces. Its direction varies over time and location. | Varies with time and place, forms the basis for magnetic bearings in compass surveying. |

| Grid Meridian | A straight line parallel to a central meridian or reference meridian established for a large-scale grid system (e.g., UTM grid). | Used in grid coordinate systems, simplifies calculations in mapping. |

| Arbitrary Meridian | Any convenient direction chosen for a local survey. It is chosen for a specific project and has no relation to true north or magnetic north. | Assumed direction for small surveys, useful when no other fixed reference is available. |

Bearing Systems: Quantifying Direction

Bearing is the horizontal angle measured from a reference meridian to a survey line. There are primary systems for expressing bearings, each with specific conventions.

Whole Circle Bearing (WCB)

| Description | Range | Measurement Direction |

|---|---|---|

| The horizontal angle measured clockwise from the North meridian to the survey line. | 0° to 360° | ⬆️➡️⬇️⬅️⬆️ (Clockwise from North) |

Reduced Bearing (RB) / Quadrantal Bearing (QB)

| Description | Range | Quadrant Specification |

|---|---|---|

| The acute angle measured from the nearest meridian (North or South) towards the East or West. | 0° to 90° | N-E, S-E, S-W, N-W (e.g., N30°E) |

Fore Bearing (FB) & Back Bearing (BB)

| Concept | Definition | Relationship (for a line AB) |

|---|---|---|

| Fore Bearing (FB) | The bearing of a survey line measured in the direction of progression (e.g., from A to B). | FBAB |

| Back Bearing (BB) | The bearing of the same line measured in the opposite direction (e.g., from B to A). | BBAB = FBAB ± 180° (Use + if FB < 180°; Use – if FB > 180°) |

| Included Angle | The interior or exterior angle between two adjacent survey lines in a traverse. | Can be calculated from the bearings of the adjacent lines. |

Traverse: The Backbone of Compass Surveying

A traverse is a series of connected survey lines whose lengths and directions are measured. It forms the framework for mapping an area, with each control point established using both linear and angular measurements.

| Traverse Type | Description | Key Characteristic / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Closed Traverse | A traverse that either starts from a known point and ends at the same point, or starts from a known point and ends at another known point (with known coordinates). | Allows for checking angular and linear errors, suitable for boundaries, pipelines, buildings. |

| Open Traverse | A traverse that starts from a known point but ends at an unknown location. No direct closing check is possible. | Used for mapping linear features like roads, railways, canals, rivers. Less accurate as errors accumulate. |

Local Attraction & Its Corrections

Local attraction refers to the disturbance of the magnetic needle from its normal magnetic meridian due to the presence of local magnetic influences. This causes incorrect magnetic bearings.

| Concept | Detection | Correction Method |

|---|---|---|

| Local Attraction | Deviation of the magnetic needle from the true magnetic meridian due to magnetic substances (iron ore, steel structures, electric wires). | Detected when the difference between Fore Bearing (FB) and Back Bearing (BB) of a line is NOT exactly 180°. |

| Correction | If FB – BB ≠ 180°, local attraction is present at either or both stations. | Identify unaffected stations (where FB-BB=180°). Correct bearings from affected stations by adjusting them based on the error observed at undisturbed lines. |

Advantages & Disadvantages of Compass Surveying

Compass surveying offers specific benefits and drawbacks that influence its applicability in various construction scenarios.

| Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Relatively fast for fieldwork, especially in open areas. | Accuracy can be compromised by speed if not careful. |

| Simplicity | Instruments are simple to operate. | Requires frequent checks for local attraction. |

| Cost | Equipment is generally less expensive than more advanced instruments. | Not suitable for highly precise work or large, complex areas. |

| Terrain | Adaptable to moderately undulating terrain. | Magnetic disturbances (local attraction) can significantly affect accuracy. |

| Obstacles | Can be used in areas with some obstacles where direct chaining might be difficult. | Visibility of previous station is often required for traverse, which can be an issue. |