Surveying is the foundational discipline for all civil engineering projects, encompassing the art and science of accurately determining the relative positions of points on, above, or beneath the Earth’s surface. It involves precise measurements of distances, angles, and elevations, which are then used to generate accurate maps, plans, and detailed layouts. For civil engineers, a deep understanding of surveying principles ensures the accuracy and precision vital for every stage of construction and infrastructure development, from initial conceptualization to final execution and beyond.

Core Purpose and Objective of Surveying

The primary objective of surveying is to obtain and process spatial data to produce a reliable and accurate representation of physical features and their relative positions. This data is indispensable for creating detailed topographical maps, cadastral plans, and engineering drawings. Ultimately, surveying facilitates the precise layout of civil engineering works, establishes legal boundaries, manages land information systems, and ensures that structures are constructed exactly according to design specifications, minimizing errors and optimizing resource utilization.

Fundamental Principles Guiding Surveying Operations

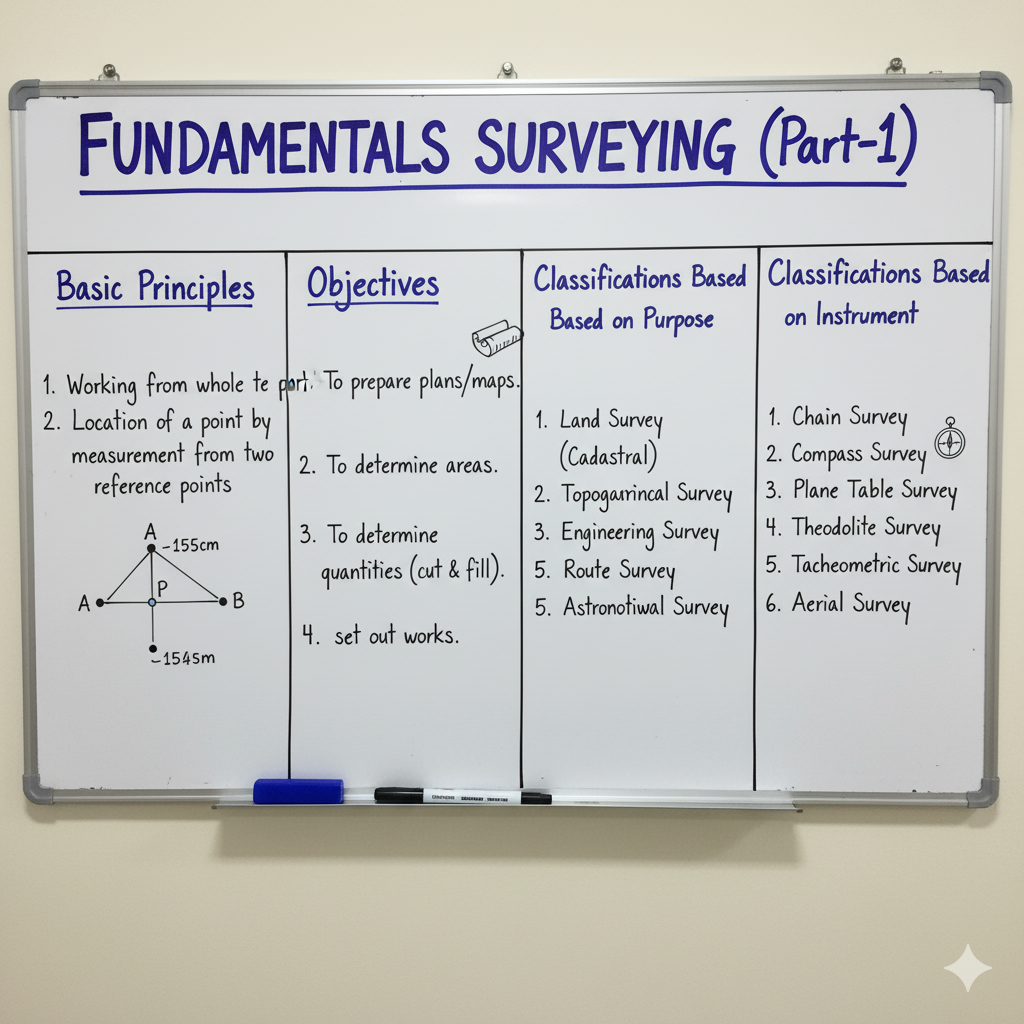

All surveying activities are meticulously governed by core principles to ensure the integrity, accuracy, and reliability of the acquired data. Adherence to these principles is paramount for minimizing the accumulation and propagation of errors throughout the survey process.

| Principle | Description | Conceptual Diagram |

|---|---|---|

| Working from Whole to Part | This fundamental principle dictates that a survey should commence by establishing a high-precision control network over a large area (the ‘whole’), followed by more detailed measurements within smaller sections (the ‘parts’). This methodology prevents the accumulation of errors by localizing any minor discrepancies within the smaller areas, ensuring overall accuracy. | 🌐➡️🏞️ |

| Fixing a Point from at least Two Measurements | Every new point whose position is to be determined must be fixed by at least two independent and accurate measurements from already established and known control points. These measurements can include two distances, one distance and one angle, or two angles. This redundancy provides an essential geometric check against potential errors. | 📍📏📐 |

| Independent Checks | Integral to quality assurance, this principle mandates that all survey work must incorporate independent checks to promptly detect mistakes and systematic errors. Employing redundant measurements, utilizing alternative measurement techniques, or verifying calculations through different approaches are common strategies to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the collected data. | ✅🔄 |

Essential Instruments Employed in Modern Surveying

Surveyors rely on a diverse array of sophisticated instruments, each designed for precise measurement of specific parameters. These tools have undergone significant technological evolution, enhancing accuracy and efficiency in data collection.

| Instrument | Description & Function | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| Measuring Tapes & Chains | Fundamental tools used for direct measurement of linear distances. Tapes are typically made of steel, linen, or fiberglass, while chains consist of interconnected metallic links. They are essential for baseline measurements and detailing. | Linear distance measurement |

| Theodolite | A highly precise optical instrument designed for accurately measuring both horizontal and vertical angles. It forms the backbone of angular measurements in triangulation, traverse, and alignment works. | Angular measurement (horizontal & vertical) |

| Total Station | An advanced electronic/optical instrument that integrates an electronic theodolite for angle measurement with an Electronic Distance Meter (EDM). It can measure angles, distances, and elevation differences, and often has onboard data storage and processing capabilities. | Combined angle, distance & elevation measurement |

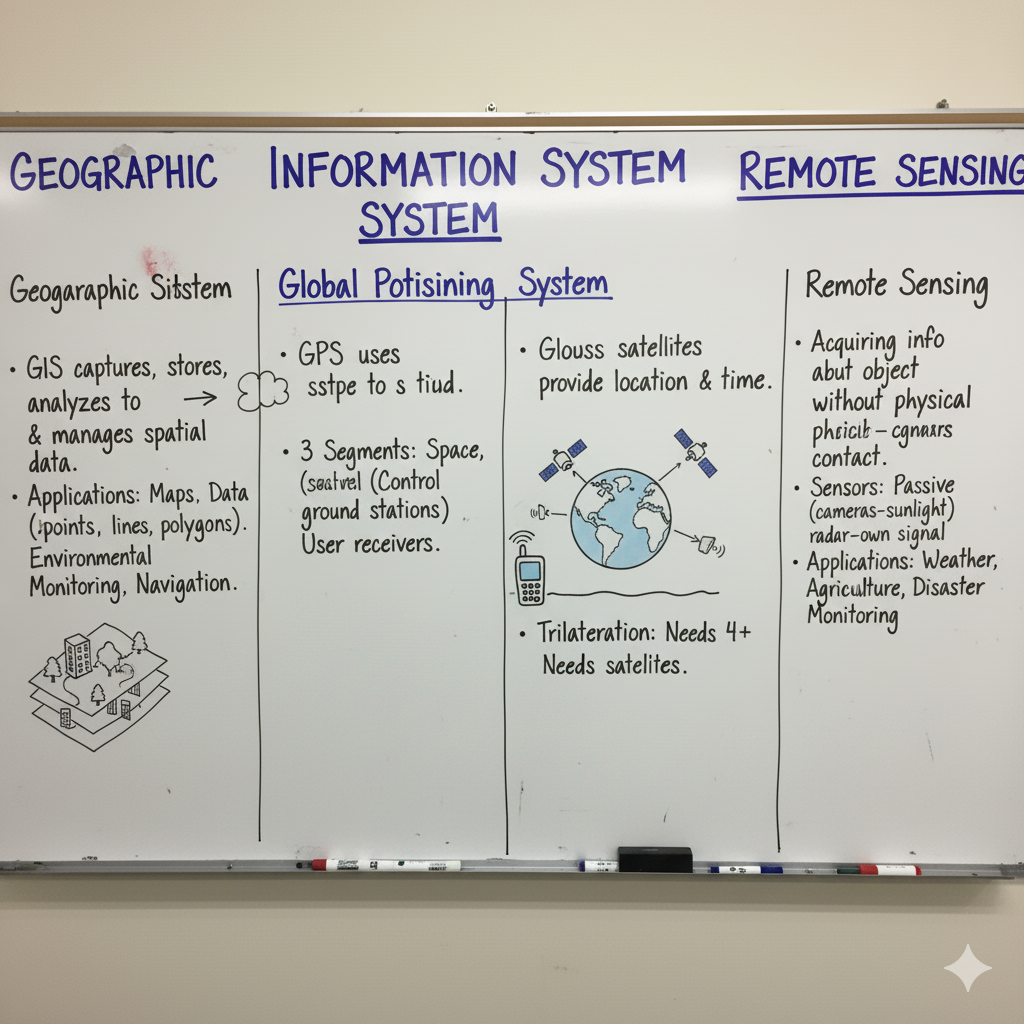

| GPS/GNSS Receivers | Global Positioning System (GPS) or Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers determine precise geographical positions (latitude, longitude, altitude) by receiving signals from orbiting satellites. They are crucial for large-scale control surveys and navigation. | Global positioning & control surveys |

| Levelling Instrument (e.g., Dumpy Level, Auto Level) | Instruments used to measure differences in elevation between points on the Earth’s surface. They establish horizontal lines of sight to determine relative heights, essential for creating contour maps, setting grades, and ensuring proper drainage. | Vertical distance measurement & elevation determination |

Classification of Surveying Disciplines

Surveying is categorized based on various factors, including the consideration of Earth’s curvature, the purpose of the survey, and the instruments employed. These classifications dictate the methods, precision levels, and computational complexities involved.

| Type of Surveying | Key Characteristic & Scope | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Geodetic Surveying | Accounts for the true spheroidal shape (curvature) of the Earth. It deals with large areas where the Earth’s curvature significantly impacts measurements, requiring advanced geodetic calculations and high precision. | National mapping, precise control networks, international boundaries. |

| Plane Surveying | Assumes the Earth’s surface is a flat plane, ignoring its curvature. This method is suitable for surveys over relatively small areas where the effect of Earth’s curvature is negligible, simplifying calculations. | Most civil engineering projects (building layout, road sections), small-scale mapping, property surveys. |

| Topographical Surveying | Focuses on determining the positions of both natural (e.g., rivers, hills) and artificial (e.g., roads, buildings) features, including their elevations, to create detailed maps showing contours and terrain relief. | Site planning, architectural design, environmental impact assessments, land development. |

| Engineering Surveying | Specific surveys conducted for the entire lifecycle of engineering projects. This includes preliminary surveys for design, layout surveys for construction, and control surveys for monitoring. | Roads, bridges, dams, buildings, pipelines, tunnels, and large-scale infrastructure. |

| Cadastral Surveying | Involves determining property lines, areas, and boundaries for legal purposes, such as land ownership, property deeds, and taxation. | Land registration, property disputes, urban and rural land management. |

| Hydrographic Surveying | Focuses on measuring and mapping the features of oceans, lakes, rivers, and other water bodies. It includes depths, coastlines, currents, and bottom topography. | Navigation chart production, port and harbor development, dredging operations. |

Diverse Applications of Surveying in Civil Engineering

The data and techniques derived from surveying are integral to nearly every phase of a civil engineering project, from initial conceptualization to ongoing maintenance.

| Application Area | Description | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Site Selection & Planning | Conducting comprehensive surveys to analyze topography, existing features, and potential challenges of a proposed site. This data is critical for evaluating suitability and preliminary design. | Optimal site utilization, early identification of design constraints. |

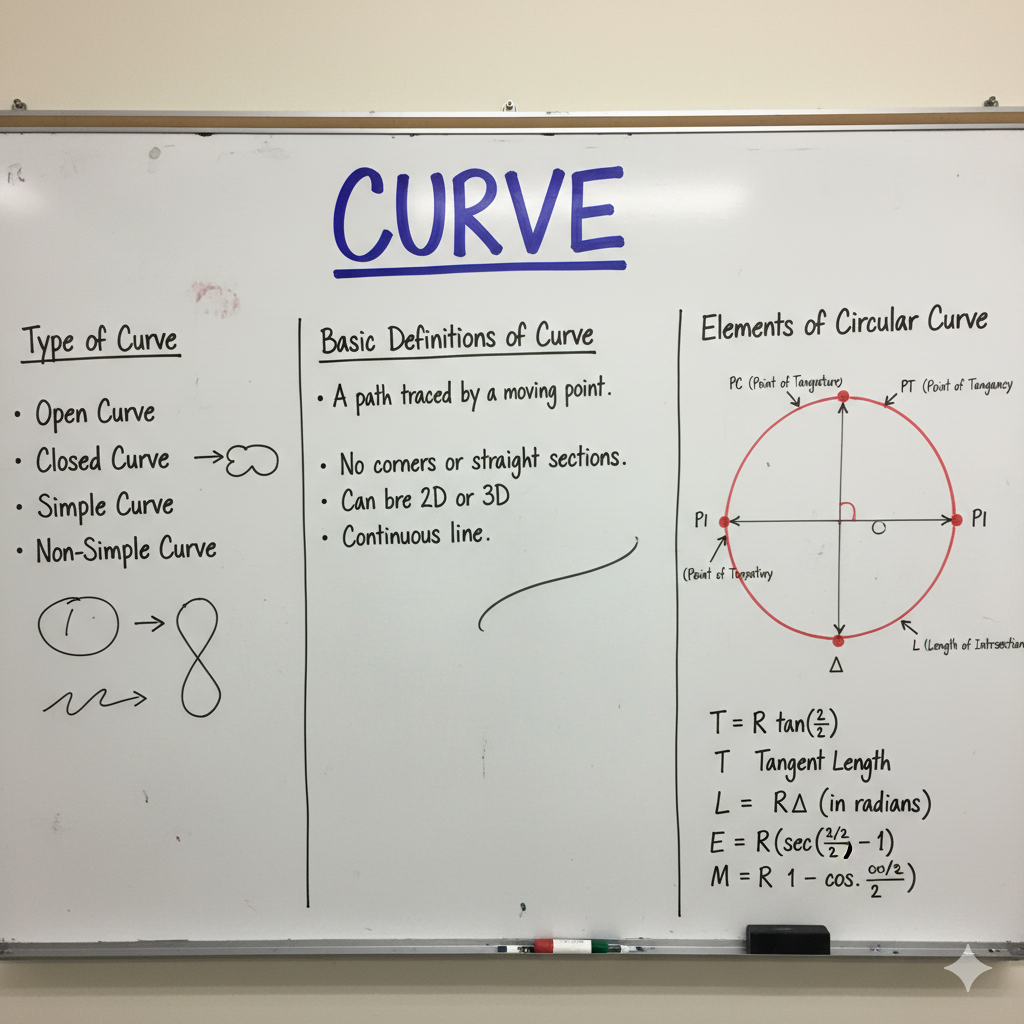

| Road & Railway Alignment | Determining the most efficient and safe routes, gradients, and curve designs for transportation networks, considering terrain, existing infrastructure, and environmental factors. | Efficient transport routes, minimized earthwork, reduced construction costs. |

| Water Resource Projects | Essential for the design and construction of hydraulic structures such as dams, canals, reservoirs, irrigation systems, and water supply networks. It involves mapping catchment areas and cross-sections. | Effective water management, flood control, irrigation efficiency. |

| Construction Layout | Precisely transferring design points and lines from plans and drawings to the actual ground. This ensures accurate placement of foundations, columns, beams, and other structural components. | Dimensional accuracy, structural stability, compliance with design. |

| Land Management & Cadastral Surveys | Defining and re-establishing property boundaries, land subdivision, and detailed mapping for legal ownership, taxation, and urban/rural development planning. | Legal clarity of land parcels, equitable land distribution, informed urban planning. |

| Volume Calculation & Earthwork | Estimating quantities of earthwork, including excavation (cuts) and filling, for grading, site preparation, and material quantity take-offs. This is crucial for accurate cost estimation. | Precise material quantity take-offs, optimized excavation/fill operations. |

| Monitoring Structural Deformation | Repeated precise surveys of existing structures to detect and monitor any settlement, displacement, or deformation over time. This is critical for assessing structural health and safety. | Early detection of structural issues, ensuring long-term safety and stability. |